What Animal Phylum Do Leeches Belong In?

| Leech Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hirudo medicinalis sucking blood | |

| |

| Helobdella sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Clitellata |

| Subclass: | Hirudinea Lamarck, 1818 |

Leeches are segmented parasitic or predatory worms that comprise the bracket Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the oligochaetes, which include the earthworm, and like them have soft, muscular, segmented bodies that tin can lengthen and contract. Both groups are hermaphrodites and have a clitellum, but leeches typically differ from the oligochaetes in having suckers at both ends and in having band markings that do not correspond with their internal segmentation. The trunk is muscular and relatively solid, and the coelom, the spacious torso cavity institute in other annelids, is reduced to small channels.

The bulk of leeches live in freshwater habitats, while some species tin be plant in terrestrial or marine environments. The best-known species, such every bit the medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis, are hematophagous, attaching themselves to a host with a sucker and feeding on claret, having first secreted the peptide hirudin to foreclose the blood from clotting. The jaws used to pierce the skin are replaced in other species by a proboscis which is pushed into the skin. A minority of leech species are predatory, mostly preying on pocket-size invertebrates.

The eggs are enclosed in a cocoon, which in aquatic species is unremarkably attached to an underwater surface; members of one family, Glossiphoniidae, exhibit parental care, the eggs being brooded by the parent. In terrestrial species, the cocoon is often concealed under a log, in a cleft or buried in damp soil. Almost seven hundred species of leech are currently recognised, of which some hundred are marine, 90 terrestrial and the remainder freshwater.

Leeches have been used in medicine from ancient times until the 19th century to describe blood from patients. In mod times, leeches find medical use in handling of joint diseases such as epicondylitis and osteoarthritis, extremity vein diseases, and in microsurgery, while hirudin is used as an anticoagulant drug to care for blood-clotting disorders.

Diverseness and phylogeny

Some 680 species of leech accept been described, of which effectually 100 are marine, 480 freshwater and the remainder terrestrial.[2] [3] Amongst Euhirudinea, the true leeches, the smallest is about 1 cm ( 1⁄ii in) long, and the largest is the giant Amazonian leech, Haementeria ghilianii, which can reach thirty cm (12 in). Except for Antarctica,[2] leeches are constitute throughout the earth but are at their most abundant in temperate lakes and ponds in the northern hemisphere. The majority of freshwater leeches are constitute in the shallow, vegetated areas on the edges of ponds, lakes and ho-hum-moving streams; very few species tolerate fast-flowing water. In their preferred habitats, they may occur in very high densities; in a favourable environment with h2o high in organic pollutants, over x,000 individuals were recorded per square metre (over 930 per square pes) nether rocks in Illinois. Some species aestivate during droughts, burying themselves in the sediment, and can lose upward to 90% of their bodyweight and withal survive.[iv] Among the freshwater leeches are the Glossiphoniidae, dorso-ventrally flattened animals mostly parasitic on vertebrates such as turtles, and unique amid annelids in both brooding their eggs and carrying their young on the underside of their bodies.[5]

The terrestrial Haemadipsidae are mostly native to the tropics and subtropics,[6] while the aquatic Hirudinidae have a wider global range; both of these feed largely on mammals, including humans.[four] A distinctive family is the Piscicolidae, marine or freshwater ectoparasites importantly of fish, with cylindrical bodies and usually well-marked, bell-shaped, anterior suckers.[vii] Not all leeches feed on blood; the Erpobdelliformes, freshwater or amphibious, are carnivorous and equipped with a relatively big, toothless mouth to ingest insect larvae, molluscs, and other annelid worms, which are swallowed whole.[8] In turn, leeches are prey to fish, birds, and invertebrates.[9]

The name for the subclass, Hirudinea, comes from the Latin hirudo (genitive hirudinis), a leech; the chemical element -bdella found in many leech group names is from the Greek βδέλλα bdella, also meaning leech.[10] The name Les hirudinées was given by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in 1818.[11] Leeches were traditionally divided into two infraclasses, the Acanthobdellidea (primitive leeches) and the Euhirudinea (true leeches).[12] The Euhirudinea are divided into the proboscis-bearing Rhynchobdellida and the residue, including some jawed species, the "Arhynchobdellida", without a proboscis.[13]

The phylogenetic tree of the leeches and their annelid relatives is based on molecular assay (2019) of Deoxyribonucleic acid sequences. Both the former classes "Polychaeta" (bristly marine worms) and "Oligochaeta" (including the earthworms) are paraphyletic: in each case the complete groups (clades) would include all the other groups shown below them in the tree. The Branchiobdellida are sister to the leech clade Hirudinida, which approximately corresponds to the traditional subclass Hirudinea. The primary subdivision of leeches is into the Rhynchobdellida and the Arhynchobdellida, though the Acanthobdella are sister to the clade that contains these two groups.[13]

Development

The most ancient annelid group consists of the free-living polychaetes that evolved in the Cambrian period, beingness plentiful in the Burgess Shale nearly 500million years ago. Oligochaetes evolved from polychaetes and the leeches branched off from the oligochaetes..[14] The oldest leech fossils are from the Jurassic period effectually 150million years ago, but a fossil with external band markings institute in Wisconsin in the 1980s, with what appears to be a large sucker, seems to extend the grouping'southward evolutionary history dorsum to the Silurian, some 437million years ago.[15] [xvi]

Anatomy and physiology

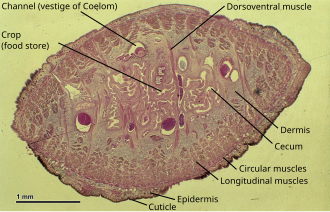

Leeches show a remarkable similarity to each other in morphology, very different from typical annelids which are cylindrical with a fluid-filled space, the coelom (body crenel). In leeches, the coelom is reduced to 4 slender longitudinal channels, and the interior of the trunk is filled with a solid dermis in between the diverse organs. Typically, the body is dorso-ventrally flattened and tapers at both ends. Longitudinal and circular muscles in the trunk wall are supplemented by diagonal muscles, giving the leech the power to adopt a large range of body shapes and bear witness great flexibility. Most leeches have a sucker at both the anterior (forepart) and posterior (back) ends, but some primitive leeches take a single sucker at the back.[17] [xviii]

Leech anatomy in cantankerous-section: the body is solid, the coelom (trunk cavity) reduced to channels, with circular, longitudinal, and transverse muscles making the animal strong and flexible.[xix]

Similar other annelids, the leech is a segmented animal, simply unlike other annelids, the segmentation is masked by external band markings (annulations).[20] The number of annulations varies, both between different regions of the body and between species.[17] In one species, the body surface is divided into 102 annuli,[21] but the body consists of 33 segments, a number abiding across all leech species. Of these segments, the offset five are designated as the head and include the inductive brain, several ocelli (eyespots) dorsally and the sucker ventrally. The following 21 mid-body segments each contain a nerve ganglion, and between them contain 2 reproductive organs, a single female person gonopore and ix pairs of testes. The last seven segments contain the posterior brain and are fused to class the animal'southward tail sucker.[17]

The body wall consists of a cuticle, an epidermis and a thick layer of fibrous connective tissue in which are embedded the circular muscles, the diagonal muscles and the powerful longitudinal muscles. In that location are besides dorso-ventral muscles. The coelomic channels run the total length of the body, the two main ones existence on either side; these have taken over the function of the hemal arrangement (blood vessels) in other annelids. Part of the lining epithelium consists of chloragogen cells which are used for the storage of nutrients and in excretion. There are 10 to 17 pairs of metanephridia (excretory organs) in the mid-region of the leech. From these, ducts typically lead to a urinary float, which empties to the outside at a nephridiopore.[19]

Reproduction and development

Leeches are protandric hermaphrodites, with the male person reproductive organs, the testes, maturing beginning and the ovaries later on. In hirudinids, a pair will line upwards with the clitellar regions in contact, with the anterior end of one leech pointing towards the posterior end of the other; this results in the male person gonopore of one leech being in contact with the female gonopore of the other. The penis passes a spermatophore into the female gonopore and sperm is transferred to, and probably stored in, the vagina.[22]

Some jawless leeches (Rhynchobdellida) and proboscisless leeches (Arhynchobdellida) lack a penis, and in these, sperm is passed from one individual to another by hypodermic injection. The leeches intertwine and grasp each other with their suckers. A spermatophore is pushed by one through the integument of the other, usually into the clitellar region. The sperm is liberated and passes to the ovisacs, either through the coelomic channels or interstitially through specialist "target tissue" pathways.[22]

Some fourth dimension after copulation, the pocket-size, relatively yolkless eggs are laid. In most species, an albumin-filled cocoon is secreted past the clitellum and receives one or more eggs as it passes over the female gonopore.[22] In the example of the North American Erpobdella punctata, the clutch size is about 5 eggs, and some 10 cocoons are produced.[23] Each cocoon is fixed to a submerged object, or in the instance of terrestrial leeches, deposited under a stone or buried in damp soil. The cocoon of Hemibdella soleae is attached to a suitable fish host.[22] [24] The glossiphoniids brood their eggs, either past attaching the cocoon to the substrate and roofing it with their ventral surface, or by securing the cocoon to their ventral surface, and fifty-fifty carrying the newly hatched young to their first meal.[25]

When breeding, near marine leeches get out their hosts and become gratis-living in estuaries. Here they produce their cocoons, after which the adults of most species die. When the eggs hatch, the juveniles seek out potential hosts when these approach the shore.[25] Leeches generally have an annual or biannual life cycle.[22]

Feeding and digestion

Nigh 3 quarters of leech species are parasites that feed on the blood of a host, while the rest are predators. Leeches either accept a throat that they can protrude, normally called a proboscis, or a pharynx that they cannot protrude, which in some groups is armed with jaws.[26]

In the proboscisless leeches, the jaws (if any) of Arhynchobdellids are at the front end of the mouth, and have 3 blades set at an angle to each other. In feeding, these slice their way through the skin of the host, leaving a Y-shaped incision. Backside the blades is the oral fissure, located ventrally at the anterior finish of the torso. Information technology leads successively into the throat, a curt oesophagus, a crop (in some species), a stomach and a hindgut, which ends at an anus located just above the posterior sucker. The stomach may be a unproblematic tube, but the ingather, when nowadays, is an enlarged part of the midgut with a number of pairs of ceca that shop ingested claret. The leech secretes an anticoagulant, hirudin, in its saliva which prevents the blood from clotting before ingestion.[26] A mature medicinal leech may feed only twice a year, taking months to assimilate a blood meal.[18]

Leech bites on a cow'due south udder

The bodies of predatory leeches are similar, though instead of a jaw many accept a protrusible proboscis, which for well-nigh of the time they go along retracted into the mouth. Such leeches are often deadfall predators that lie in expect until they can strike prey with the proboscises in a spear-like manner.[27] Predatory leeches feed on modest invertebrates such every bit snails, earthworms and insect larvae. The prey is usually sucked in and swallowed whole. Some Rhynchobdellida nevertheless suck the soft tissues from their prey, making them intermediate betwixt predators and blood-suckers.[26]

Claret-sucking leeches utilize their inductive suckers to connect to hosts for feeding. In one case fastened, they apply a combination of mucus and suction to stay in place while they inject hirudin into the hosts' blood. In full general, claret-feeding leeches are non host-specific, and practice lilliputian impairment to their host, dropping off after consuming a blood meal. Some marine species however remain attached until it is time to reproduce. If nowadays in great numbers on a host, these can be debilitating, and in extreme cases, crusade death.[25]

Leeches are unusual in that they do not produce sure digestive enzymes such as amylases, lipases or endopeptidases.[26] A deficiency of these enzymes and of B complex vitamins is compensated for by enzymes and vitamins produced by endosymbiotic microflora. In Hirudo medicinalis, these supplementary factors are produced past an obligatory mutualistic relationship with the bacterial species, Aeromonas veronii. Non-bloodsucking leeches, such every bit Erpobdella octoculata, are host to morew bacterial symbionts.[28] In addition, leeches produce intestinal exopeptidases which remove amino acids from the long poly peptide molecules i by ane, perhaps aided past proteases from endosymbiotic bacteria in the hindgut.[29] This evolutionary selection of exopeptic digestion in Hirudinea distinguishes these carnivorous clitellates from oligochaetes, and may explain why digestion in leeches is then slow.[26]

Nervous system

A leech'due south nervous system is formed of a few large nerve cells; their large size makes leeches user-friendly as model organisms for the study of invertebrate nervous systems. The main nerve center consists of the cerebral ganglion in a higher place the gut and another ganglion below it, with connecting nerves forming a ring around the throat a fiddling way behind the mouth. A nerve string runs backwards from this in the ventral coelomic channel, with 21 pairs of ganglia in segments six to 26. In segments 27 to 33, other paired ganglia fuse to class the caudal ganglion.[30] Several sensory nerves connect straight to the cognitive ganglion; there are sensory and motor nerve cells connected to the ventral nerve cord ganglia in each segment.[18]

Leeches have between ii and 10 paint spot ocelli, arranged in pairs towards the front of the torso. There are also sensory papillae arranged in a lateral row in one annulation of each segment. Each papilla contains many sensory cells. Some rhynchobdellids have the power to modify colour dramatically past moving paint in chromatophore cells; this process is under the control of the nervous system just its function is unclear equally the change in hue seems unrelated to the colour of the surroundings.[xxx]

Leeches can detect touch, vibration, movement of nearby objects, and chemicals secreted by their hosts; freshwater leeches crawl or swim towards a potential host standing in their swimming within a few seconds. Species that feed on warm-blooded hosts motility towards warmer objects. Many leeches avoid light, though some blood feeders move towards low-cal when they are set up to feed, presumably increasing the chances of finding a host.[18]

Gas exchange

Leeches alive in damp surround and in full general respire through their body wall. The exception to this is in the Piscicolidae, where branching or leafage-like lateral outgrowths from the body wall form gills. Some rhynchobdellid leeches accept an extracellular haemoglobin pigment, merely this but provides for about half of the leech's oxygen transportation needs, the rest occurring by improvidence.[xix]

Movement

Leeches move using their longitudinal and round muscles in a modification of the locomotion past peristalsis, self-propulsion by alternately contracting and lengthening parts of the body, seen in other annelids such as earthworms. They use their posterior and anterior suckers (one on each finish of the trunk) to enable them to progress by looping or inching along, in the mode of geometer moth caterpillars. The posterior stop is attached to the substrate, and the inductive end is projected forward peristaltically by the round muscles until it touches down, as far equally information technology can attain, and the inductive stop is fastened. And then the posterior stop is released, pulled forward by the longitudinal muscles, and reattached; then the anterior end is released, and the cycle repeats.[31] [18] Leeches explore their surround with head movements and body waving.[32] The Hirudinidae and Erpobdellidae tin can swim apace with up-and-down or sideways undulations of the trunk; the Glossiphoniidae in contrast are poor swimmers and curl upwardly and autumn to the sediment below when disturbed.[33]

-

Video of looping move

Interactions with humans

Leeches tin exist removed by hand, since they do not couch into the skin or leave the head in the wound.[34] [35]

Bites

Leech bites are more often than not alarming rather than unsafe, though a small percentage of people take severe allergic or anaphylactic reactions and require urgent medical care. Symptoms of these reactions include red blotches or an itchy rash over the body, swelling around the lips or eyes, a feeling of faintness or dizziness, and difficulty in breathing.[36] An externally attached leech volition detach and fall off on its own accord when it is satiated on blood, which may take from twenty minutes to a few hours; bleeding from the wound may continue for some fourth dimension.[36] Internal attachments, such as within the nose, are more likely to require medical intervention.[37]

Bacteria, viruses, and protozoan parasites from previous blood sources tin can survive inside a leech for months, and then leeches could potentially act as vectors of pathogens. Notwithstanding, only a few cases of leeches transmitting pathogens to humans have been reported.[38] [39]

Leech saliva is usually believed to incorporate anaesthetic compounds to numb the bite area, but this has never been proven.[40] Although morphine-like substances have been establish in leeches, they have been found in the neural tissues, not the salivary tissues. They are used past the leeches in modulating their own immunocytes and not for anaesthetising bite areas on their hosts.[41] [forty] Depending on the species and size, leech bites tin can be barely noticeable or they can be adequately painful.[42] [43]

In human culture

The leech appears in Proverbs30:15 equally an classic of clamorous greed.[44] More generally, a leech is a persistent social parasite or sycophant.[45]

The medicinal leech Hirudo medicinalis, and another species, have been used for clinical bloodletting for at to the lowest degree 2,500 years: Ayurvedic texts draw their employ for bloodletting in ancient Republic of india. In ancient Greece, bloodletting was practised co-ordinate to the theory of humours found in the Hippocratic Corpus of the fifth centuryBC, which maintained that wellness depended on a balance of the four humours: claret, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. Bloodletting using leeches enabled physicians to restore residue if they considered blood was present in excess.[46] [47]

Pliny the Elder reported in his Natural History that the horse leech could drive elephants mad by climbing up within their trunks to drink claret.[48] Pliny also noted the medicinal use of leeches in ancient Rome, stating that they were often used for gout, and that patients became addicted to the handling.[49] In Old English, lǣce was the name for a physician likewise as for the animal, though the words had different origins, and lǣcecraft, leechcraft, was the art of healing.[fifty]

-

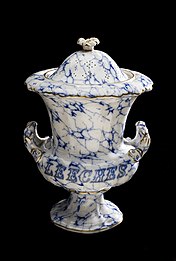

Chemist's shop leech jar with airholes in the chapeau. England, 1830–1870.

William Wordsworth'south 1802 poem "Resolution and Independence" describes one of the concluding of the leech-gatherers, people who travelled United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland catching leeches from the wild, and causing a abrupt decline in their affluence, though they remain numerous in Romney Marsh. By 1863, British hospitals had switched to imported leeches, some seven million being imported to hospitals in London that yr.[48]

In the nineteenth century, need for leeches was sufficient for hirudiculture, the farming of leeches, to get commercially feasible.[51] Leech usage declined with the demise of humoral theory,[52] but made a small-scale comeback in the 1980s later years of decline, with the advent of microsurgery, where venous congestion tin ascend due to inefficient venous drainage. Leeches can reduce swelling in the tissues and promote healing, helping in particular to restore circulation after microsurgery to reattach body parts.[53] [54] Other clinical applications include varicose veins, muscle cramps, thrombophlebitis, and joint diseases such equally epicondylitis and osteoarthritis.[55] [56] [57] [58]

Leech secretions contain several bioactive substances with anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant and antimicrobial furnishings.[57] One active component of leech saliva is a minor protein, hirudin.[59] It is widely used as an anticoagulant drug to care for blood-clotting disorders, and manufactured past recombinant DNA technology.[60] [61]

In 2012 and 2018, Ida Schnell and colleagues trialled the utilize of Haemadipsa leeches to assemble data on the biodiversity of their mammalian hosts in the tropical rainforest of Vietnam, where information technology is hard to obtain reliable data on rare and ambiguous mammals. They showed that mammal mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic acid, amplified past the polymerase chain reaction, can be identified from a leech'due south blood meal for at least iv months subsequently feeding. They detected Annamite striped rabbit, small-scale-toothed ferret-badger, Truong Son muntjac, and serow in this mode.[62] [63]

Water pollution

Exposure to synthetic estrogen as used in contraceptive medicines, which may enter freshwater ecosystems from municipal wastewater, can affect leeches' reproductive systems. Although not as sensitive to these compounds as fish, leeches showed physiological changes afterwards exposure, including longer sperm sacs and vaginal bulbs, and decreased epididymis weight.[64]

Notes

- ^ The explanation below the lithograph reads "There'southward redundancy of blood and humours, we'll bleed you to-morrow, till and so, very picayune food."

References

- ^ Chiangkul, Krittiya; Trivalairat, Poramad; Purivirojkul, Watchariya (2018). "Redescription of the Siamese shield leech Placobdelloides siamensis with new host species and geographic range". Parasite. 25: 56. doi:10.1051/parasite/2018056. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC6254108. PMID 30474597.

- ^ a b Sket, Boris; Trontelj, Peter (2008). "Global diversity of leeches (Hirudinea) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 129–137. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9010-8. S2CID 46339662.

- ^ Fogden, S.; Proctor, J. (1985). "Notes on the Feeding of Land Leeches (Haemadipsa zeylanica Moore and H. picta Moore) in Gunung Mulu National Park, Sarawak". Biotropica. 17 (two): 172–174. doi:10.2307/2388511. JSTOR 2388511.

- ^ a b Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 471

- ^ Siddall, Mark Due east. (1998). "Glossiphoniidae". American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved ane May 2018. }}

- ^ Ruppert, Trick & Barnes 2004, p. 480

- ^ Meyer, Marvin C. (July 1940). "A Revision of the Leeches (Piscicolidae) Living on Fresh-Water Fishes of Northward America". Transactions of the American Microscopical Gild. 59 (3): 354–376. doi:x.2307/3222552. JSTOR 3222552.

- ^ Oceguera, A.; Leon, V.; Siddall, Yard. (2005). "Phylogeny and revision of Erpobdelliformes (Annelida, Arhynchobdellida) from United mexican states based on nuclear and mitochondrial cistron sequences". Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad. 76 (2): 191–198. doi:10.22201/ib.20078706e.2005.002.307 . Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Leeches". Australian Museum. 14 November 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Scarborough, John (1992). Medical and Biological Terminologies: Classical Origins. Academy of Oklahoma Press. p. 58. ISBN978-0-8061-3029-3.

- ^ Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1818). Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres ... précédée d'une introduction offrant la détermination des caractères essentiels de l'animate being, sa distinction du végétal et des autres corps naturels, enfin, l'exposition des principes fondamentaux de la zoologie. Volume 5. Vol. v. Paris: Verdière.

- ^ Kolb, Jürgen (2018). "Hirudinea". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b Phillips, Anna J.; Dornburg, Alex; Zapfe, Katerina Fifty.; Anderson, Frank E.; James, Samuel W.; Erséus, Christer; Moriarty Lemmon, Emily; Lemmon, Alan R.; Williams, Bronwyn W. (2019). "Phylogenomic Analysis of a Putative Missing Link Sparks Reinterpretation of Leech Evolution". Genome Biological science and Development. eleven (11): 3082–3093. doi:x.1093/gbe/evz120. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC6598468. PMID 31214691.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Chapman, Michael J. (2009). Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on World. Bookish Printing. p. 308. ISBN978-0-08-092014-6.

- ^ Thorp, James H.; Covich, Alan P. (2001). Environmental and Nomenclature of North American Freshwater Invertebrates. Bookish Press. p. 466. ISBN978-0-12-690647-nine.

- ^ Mikulic, D. G.; Briggs, D. East. G.; Kluessendorf, J. (1985). "A new exceptionally preserved biota from the Lower Silurian of Wisconsin, U.S.A." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 311 (1148): 75–85. Bibcode:1985RSPTB.311...75M. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0140.

- ^ a b c Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, pp. 471–472

- ^ a b c d eastward Brusca, Richard (2016). Hirudinoidea: Leeches and Their Relatives. Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates. pp. 591–597. ISBN978-1-60535-375-3.

- ^ a b c Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, pp. 474–475

- ^ Buchsbaum, Ralph; Buchsbaum, Mildred; Pearse, John; Pearse, Vicki (1987). Animals Without Backbones (3rd ed.). The University of Chicago Press. pp. 312–317. ISBN978-0-226-07874-8.

- ^ Payton, Brian (1981). Muller, Kenneth; Nicholls, John; Stent, Gunther (eds.). Neurobiology of the Leech. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. pp. 35–50. ISBN978-0-87969-146-2.

- ^ a b c d e Ruppert, Fob & Barnes 2004, pp. 477–478

- ^ Sawyer, R. T. (1970). "Observations on the Natural History and Behavior of Erpobdella punctata (Leidy) (Annelida: Hirudinea)". The American Midland Naturalist. 83 (one): 65–80. doi:10.2307/2424006. JSTOR 2424006.

- ^ Gelder, Stuart R.; Gagnon, Nicole Fifty.; Nelson, Kerri (2002). "Taxonomic Considerations and Distribution of the Branchiobdellida (Annelida: Clitellata) on the North American Continent". Northeastern Naturalist. ix (4): 451–468. doi:10.1656/1092-6194(2002)009[0451:TCADOT]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3858556.

- ^ a b c Rohde, Klaus (2005). Marine Parasitology. CSIRO Publishing. p. 185. ISBN978-0-643-09927-2.

- ^ a b c d e Ruppert, Play a joke on & Barnes 2004, pp. 475–477

- ^ Govedich, Fredric R.; Bain, Bonnie A. (14 March 2005). "All well-nigh leeches" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ Sawyer, Roy T. "Leech biology and behaviour" (PDF). biopharm-leeches.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2011.

- ^ Dziekońska-Rynko, Janina; Bielecki, Aleksander; Palińska, Katarzyna (2009). "Activity of selected hydrolytic enzymes from leeches (Clitellata: Hirudinida) with different feeding strategies". Biologia. 64 (2): 370–376. doi:ten.2478/s11756-009-0048-0.

- ^ a b Ruppert, Fob & Barnes 2004, pp. 472–474

- ^ a b Elderberry, H. Y. (1980). Elder, H. Y.; Trueman, Due east. R. (eds.). Peristaltic Mechanisms. Order for Experimental Biology, Seminar Series: Volume v, Aspects of Brute Movement. Loving cup Archive. pp. 84–85. ISBN978-0-521-29795-0.

- ^ Sawyer, Roy (1981). Kenneth, Muller; Nicholls, John; Stent, Gunther (eds.). Neurobiology of the Leech. Cold Jump Harbor Laboratory. pp. 7–26. ISBN978-0-87969-146-ii.

- ^ Smith, Douglas Grant (2001). Pennak's Freshwater Invertebrates of the United States: Porifera to Crustacea. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 304–305. ISBN978-0-471-35837-4.

- ^ Shush, Don (2005). The complete Burke'southward backyard: the ultimate book of fact sheets. Murdoch Books. ISBN978-one-74045-739-2.

- ^ Fujimoto, Gary; Robin, Marc; Dessery, Bradford (2003). The Traveler's Medical Guide. Prairie Smoke Printing. ISBN978-0-9704482-5-5.

- ^ a b Victorian Poisons Data Centre: Leeches Victorian Poisons Data Eye. Retrieved 28 July 2007

- ^ Chow, C. 1000.; Wong, Southward. S.; Ho, A. C.; Lau, S. K. (2005). "Unilateral epistaxis after swimming in a stream". Hong Kong Medical Journal. xi (2): 110–112. PMID 15815064. See also lay summary from Reuters, xi April 2005.

- ^ Ahl-Khleif, A.; Roth, M.; Menge, C.; Heuser, J.; Baljer, G.; Herbst, Due west. (2011). "Tenacity of mammalian viruses in the gut of leeches fed with porcine blood". Journal of Medical Microbiology. lx (half-dozen): 787–792. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.027250-0. PMID 21372183.

- ^ Nehili, Malika; Ilk, Christoph; Mehlhorn, Heinz; Ruhnau, Klaus; Dick, Wolfgang; Njayou, Mounjohou (1994). "Experiments on the possible role of leeches every bit vectors of animal and human pathogens: a lite and electron microscopy study". Parasitology Inquiry. 80 (4): 277–290. doi:10.1007/bf02351867. ISSN 0044-3255. PMID 8073013. S2CID 19770060.

- ^ a b Meir, Rigbi; Levy, Haim; Eldor, Amiram; Iraqi, Fuad; Teitelbaum, Mira; Orevi, Miriam; Horovitz, Amnon; Galun, Rachel (1987). "The saliva of the medicinal leech Hirudo medicinalis—II. Inhibition of platelet aggregation and of leukocyte activity and examination of reputed anaesthetic furnishings". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 88 (i): 95–98. doi:10.1016/0742-8413(87)90052-one. PMID 2890494.

- ^ Laurent, V.; Salzet, B.; Verger-Bocquet, Chiliad.; Bernet, F.; Salzet, M. (2000). "Morphine-like substance in leech ganglia. Evidence and allowed modulation". European Journal of Biochemistry. 267 (8): 2354–2361. doi:x.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01239.x. PMID 10759861.

- ^ Siddall, Marking; Borda, Liz; Burreson, Gene; Williams, Juli. "Blood Lust II". Laboratory of Phylohirudinology, American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved fifteen December 2013.

- ^ Yi-Te Lai; Jiun-Hong Chen (2010). 臺灣蛭類動物志: Leech Animal of Taiwan-Biota Taiwanica. 國立臺灣大學出版中心. p. 89. ISBN978-986-02-2760-iv.

- ^ "Proverbs 30:15 | Ellicott's Commentary for English Readers". BibleHub. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Leech". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ Payton, Brian (1981). Muller, Kenneth; Nicholls, John; Stent, Gunther (eds.). Neurobiology of the Leech. Cold Bound Harbor Laboratory. pp. 27–34. ISBN978-0-87969-146-2.

- ^ Mory, Robert N.; Mindell, David; Bloom, David A. (2014). "The Leech and the Physician: Biological science, Etymology, and Medical Practice with Hirudinea medicinalis". World Periodical of Surgery. 24 (seven): 878–883. doi:ten.1007/s002680010141. hdl:2027.42/42411. PMID 10833259. S2CID 18166996.

- ^ a b Marren, Peter; Mabey, Richard (2010). Bugs Britannica. Chatto & Windus. pp. 45–48. ISBN978-0-7011-8180-2.

- ^ Pliny (1991). Natural History: A Selection. Translated past Healy, John F. Penguin Books. p. 283. ISBN978-0-14-044413-1.

- ^ Mory, Robert N.; Mindell, David; Bloom, David A. (2014). "The Leech and the Physician: Biology, Etymology, and Medical Practice with Hirudinea medicinalis". World Journal of Surgery. 24 (vii): 878–883. doi:ten.1007/s002680010141. hdl:2027.42/42411. ISSN 0364-2313. PMID 10833259. S2CID 18166996.

- ^ Jourdier, August; Coste, M. (March 1859). "Hirudiculture (Leech-Culture) (from La Pisciculture et la Production des Sanguesues (Fish farming and leech production). Paris : Hachette et Cie". The Journal of Agriculture. New Series. William Blackwood and Sons. 8 (July 1857–March 1859 ): 641–648.

- ^ anon (2016). Medicine: The Definitive Illustrated History. Dorling Kindersley. p. 35. ISBN978-0-241-28715-half-dozen.

- ^ Cho, Joohee (iv March 2008). "Some Docs Latching Onto Leeches". ABC News. Retrieved 27 Apr 2018.

- ^ Adams, Stephen L. (1988). "The Medicinal Leech: A Page from the Annelids of Internal Medicine". Annals of Internal Medicine. 109 (5): 399–405. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-109-5-399. PMID 3044211.

- ^ Teut, Chiliad.; Warning, A. (2008). "Leeches, phytotherapy and physiotherapy in osteo-arthrosis of the knee—a geriatric case written report". Forsch Komplementärmed. 15 (5): 269–272. doi:10.1159/000158875. PMID 19001824.

- ^ Michalsen, A.; Moebus, S.; Spahn, Thou.; Esch, T.; Langhorst, J.; Dobos, M.J. (2002). "Leech therapy for symptomatic treatment of knee osteoarthritis: Results and implications of a pilot study". Culling Therapies in Wellness and Medicine. 8 (5): 84–88. PMID 12233807.

- ^ a b Sig, A. K.; Guney, Thousand.; Uskudar Guclu, A.; Ozmen, Eastward. (2017). "Medicinal leech therapy—an overall perspective". Integrative Medicine Research. 6 (4): 337–343. doi:ten.1016/j.imr.2017.08.001. PMC5741396. PMID 29296560.

- ^ Abdualkader, A. Thou.; Ghawi, A. M.; Alaama, M.; Awang, 1000.; Merzouk, A. (2013). "Leech Therapeutic Applications". Indian Periodical of Pharmacological Science. 75 (2 (March–April)): 127–137. PMC3757849. PMID 24019559.

- ^ Haycraft, John B. (1883). "IV. On the action of a secretion obtained from the medicinal leech on the coagulation of the claret". Proceedings of the Regal Society of London. 36 (228–231): 478–487. doi:10.1098/rspl.1883.0135.

- ^ Fischer, Karl-Georg; Van de Loo, Andreas; Bohler, Joachim (1999). "Recombinant hirudin (lepirudin) as anticoagulant in intensive care patients treated with continuous hemodialysis". Kidney International. 56 (Suppl. 72): S46–S50. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.56.s72.2.x. PMID 10560805.

- ^ Sohn, J.; Kang, H.; Rao, Grand.; Kim, C.; Choi, Due east.; Chung, B.; Rhee, Due south. (2001). "Current status of the anticoagulant hirudin: its biotechnological production and clinical practice". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 57 (5–6): 606–613. doi:10.1007/s00253-001-0856-9. ISSN 0175-7598. PMID 11778867. S2CID 19304703.

- ^ Schnell, Ida Bærholm; Thomsen, Philip Francis; Wilkinson, Nicholas; Rasmussen, Morten; Jensen, Lars R. D.; Willerslev, Eske; Bertelsen, Mads F.; Gilbert, Thousand. Thomas P. (2012). "Screening mammal biodiversity using DNA from leeches". Current Biology. 22 (viii): R262–R263. doi:ten.1016/j.cub.2012.02.058. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 22537625.

- ^ Schnell, Ida Bærholm; Bohmann, Kristine (2018). Schultze, Sebastian E.; Richter, Stine R.; Murray, Dáithí C.; Sinding, Mikkel‐Holger S.; Bass, David; Cadle, John East.; Campbell, Bricklayer J.; Dolch, Rainer; Edwards, David P.; Gray, Thomas N.Eastward.; Hansen, Teis; Hoa, Anh Nguyen Quang; Noer, Christina Lehmkuhl; Heise‐Pavlov, Sigrid; Pedersen, Adam F. Sander; Ramamonjisoa, Juliot Carl; Siddall, Mark East.; Tilker, Andrew; Traeholt, Carl; Wilkinson, Nicholas; Woodcock, Paul; Yu, Douglas W.; Bertelsen, Mads Frost; Bunce, Michael; Gilbert, G. Thomas P. "Debugging multifariousness – a pan‐continental exploration of the potential of terrestrial blood‐feeding leeches equally a vertebrate monitoring tool" (PDF). Molecular Environmental Resources. 18 (6): 1282–1298. doi:ten.1111/1755-0998.12912. PMID 29877042. S2CID 46972335.

- ^ Kidd, Karen A.; Graves, Stephanie D.; McKee, Graydon I.; Dyszy, Katarzyna; Podemski, Cheryl L. (2020). "Effects of Whole-Lake Additions of Ethynylestradiol on Leech Populations". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 39 (eight): 1608–1619. doi:ten.1002/etc.4789. ISSN 1552-8618. PMID 32692460.

Full general bibliography

- Ruppert, Edward E.; Play a joke on, Richard S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology, 7th Edition. Cengage Learning. ISBN978-81-315-0104-7.

External links

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leech

Posted by: velasquezancticipse.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animal Phylum Do Leeches Belong In?"

Post a Comment